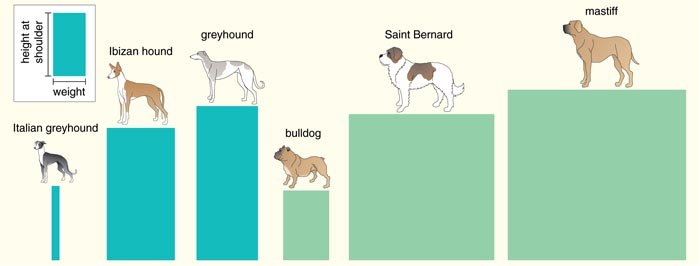

A pekingese weighs only a couple of pounds; a St. Bernard can weigh over 180. Both dogs, though vastly different in appearance, are members of the same genus and species, Canis familiaris. How dog breeds can exhibit such an enormous level of variation between breeds, and yet show strong conformity within a breed, is a question of interest to breeders and everyday dog lovers alike. In the past few years, it has also become a compelling question for mammalian geneticists.

Further, breeds often experience population bottlenecks as the popularity of the breed waxes and wanes. As a result of this population structure, genetic diseases are more common in purebred dogs than in mixed-breed dogs. Scientists have been motivated to use dog populations to find genes for diseases that affect both humans and dogs, including cancer, deafness, epilepsy, diabetes, cataracts and heart disease. In doing so we can simultaneously help man and man’s best friend.

The initial stages of the dog genome project involved the building of maps that allowed scientists to navigate the dog genome. Quick to follow were the production of resources that facilitated the manipulation of large pieces of dog genome DNA and a numbering of the dogs’ 38 pairs of autosomes (non-sex chromosomes) as well as the X and Y chromosomes. Finally, in 2003, a partial sequence of a standard poodle was produced that spanned nearly 80 percent of the 2.8 billion base pairs that make up the dog genome. This was followed quickly by a concerted effort to fully sequence the boxer genome, producing what is today the reference sequence for the dog.

How is this information being used by geneticists today? The availability of a high-quality draft sequence of the dog genome has quite literally changed the way geneticists do their work. Previously scientists used so-called “candidate gene” approaches to try and guess which genes were responsible for a particular disease or trait of interest. By knowing something about what a gene does or what family it belongs too, we can sometimes, but not always, develop excellent hypotheses as to what happens when a specific gene goes awry. However, candidate gene approaches are often characterized by frustration and great expense. Hence, companion-animal geneticists are turning increasingly to the more sophisticated genomic approaches made possible by the success of the dog genome project.

Central to our ability to use the newly available resources is an understanding of breed structure, the strengths and limitations of the current molecular resources, and consideration of the traits which are likely to lend themselves to mapping using available resources. In this article I highlight first our current understanding of what a dog breed really is and summarize the status of the canine genome sequencing project. I review some early work made possible by this project: studies of the Portuguese water dog, which have been critical to our understanding of how to map genes controlling body shape and size, along with studies aimed at understanding the genetics of muscle mass.

Dog Breeds

The American Kennel Club (AKC) currently recognizes about 155 breeds of dog, but new breeds are created and given breed-recognition status frequently. What defines a dog breed? Although a dog’s parentage can be recognized by its physical attributes—coat color, body shape and size, leg length and head shape, among others—the concept of a breed has been formally defined by both dog fanciers and geneticists.

Dog regulatory bodies such as the AKC define an individual’s breed by its parentage. For a dog to become a registered member of a breed (say, a golden retriever), both of its parents must have been registered members of the same breed, and their parents in turn must be registered golden retrievers. As a result, dog breeds in the United States today are generally closed breeding populations with little opportunity for introduction of new alleles (variations in the genome). At a genomic level, purebred dogs are usually characterized by reduced levels of genetic heterogeneity compared to mixed-breed dogs. Breeds that derive from small numbers of founders, have experienced population bottlenecks or have experienced popular-sire effects—that is, the effect on the breed of a dog who does well in shows producing a disproportionate number of litters—display further reductions in genetic heterogeneity.

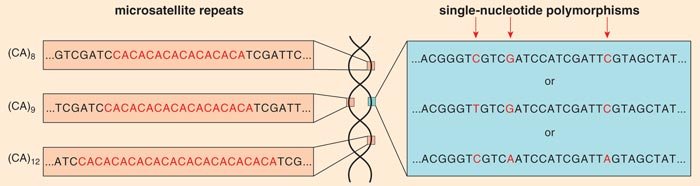

Recently, my laboratory group and others have begun to use genetic tools such as markers to define the concept of a dog breed. A genetic marker is a position in the genome where there is variability in the sequence that is inherited in a Mendelian fashion (that is, following the rules of classical genetics). Two common kinds of markers are microsatellite markers, where the variation comes from the number of times a repeat element is reiterated at a given position on a chromosome, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs, pronounced “snips”), in which the DNA sequence varies when a single nucleotide (denoted A, C, T or G) in a sequence differs between the paired chromosomes of an individual.

These alterations are proving invaluable for understanding the role of genetic modifications both within and between breeds. Because the alleles of markers are inherited from parent to child in a Mendelian fashion, they can be used to track the inheritance of adjacent pieces of DNA through the multiple generations in a family. There are thousands of microsatellite markers and millions of SNPs distributed randomly throughout the canine genome.

In order to determine the degree to which dogs could be assigned correctly to their breed group, my lab utilized data from 96 microsatellite markers spanning all the dog’s 38 autosomes in a set of 414 dogs representing 85 breeds. We found, first, that nearly all individual dogs were assigned correctly into their breed group when we used a set of statistical tools called clustering algorithms, which look for similarities in the frequency and distribution of alleles between individuals. The exceptions largely included six sets of closely related breed pairs (for example whippet-greyhound and mastiff-bullmastiff) that could only be assigned to their respective breeds when considered in isolation from other breeds.

We also showed that the genetic variation between dog breeds is much greater than the variation within breeds. Between-breed variation is estimated at 27.5 percent. By comparison, genetic variation between human populations is only 5.4 percent. Thus the concept of a dog breed is very real and can be defined not only by the dog’s appearance but genetically as well.

A second part of the study used an assignment test to determine whether we could correctly identify each dog’s breed by its genetic profile alone. In a blinded study, where the computer program did not know what data set came from which breed, 99 percent of dogs were correctly assigned to their breed based on their DNA profile alone.

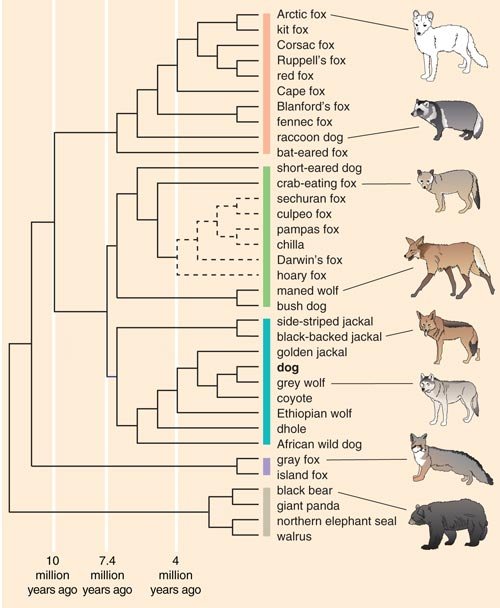

To determine the ancestral relationship between breeds, Heidi Parker from my lab used data from the same set of dogs and sought to determine, ideally, which dog breeds were most closely related to one another. To do this we utilized a computer program called structure, which was developed by Jonathan Pritchard at the University of Chicago and his colleagues. The program identifies genetically distinct subpopulations within a group based on patterns of allele frequencies, presumably from a shared ancestral pool.

The structure analysis initially ordered the 85 breeds into four clusters, generating a new canine classification system. Cluster 1 comprised dogs of Asian and African origin—thought to be older lineages—as well as gray wolves. Cluster 2 included largely mastiff-type dogs with big, boxy heads and large, sturdy bodies. The third and fourth clusters split a group of herding dogs and sight hounds away from the general population of modern hunting dogs, the latter of which includes terriers, hounds and gun dogs. As more dog breeds have been added to the study, additional groupings have emerged.

These data are extremely useful for disease-gene mapping studies. In some cases, dogs from breeds that are members of the same cluster can be analyzed simultaneously to increase the statistical power of the study. This will not only aid in the identification of genomic regions in which the disease gene lies, but will also assist in “fine mapping” studies which aim to reduce the region of DNA linkage to a manageable size of about 1 million bases. Once a region is well defined, we can begin to select candidate genes for mutation testing.

Sequencing the Dog Genome

The first published sequence of the dog genome was completed in 2003 in an effort lead by Ewen Kirkness at The Institute for Genome Research. Genomes are typically sequenced in many thousands of overlapping segments, and to ensure that the whole genome is recorded at least once, it is estimated that there have to be seven or eight iterations, or “reads,” across the entire genome. The 2003 genome, from a standard poodle, was a so-called survey sequence. The genome was sequenced just 1.5 times, so about 80 percent of the genome was present in the final data set. This work was followed shortly thereafter by the release of the draft assembly of the boxer genome, led by Kerstin Lindblad-Toh and colleagues at the Broad Institute, which was done at 7.5x density. With millions of reads successfully completed, nearly 99 percent of the genome is present in the final data set.

Both resources have proved to be extremely useful. The 1.5x sequence provided the first glimpse into the organization of the dog genome, number of genes and organization of repeat elements. One surprise was the discovery of a large number of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) littered throughout the dog genome that were occasionally located at positions with the potential to affect gene expression. For example, the insertion of a SINE element into the gene encoding the hypocretin receptor, a neuropeptide hormone found in the hypothalamus of the brain, results in the disease narcolepsy in the Doberman pinscher. Similarly, a SINE element inserted into the SILV gene (known to be related to pigmentation) is responsible for merle, the mottled patterning of a dog’s coat.

The 7.5x female boxer sequence spans most of the dog’s 2.4 billion bases in a sum total of 31.5 million sequence reads. The sequence is estimated to cover over 99 percent of the eukaryotic genome and provides data for the existence of about 19,000 genes. For about 75 percent of the genes, the homology (amount of similarity arising from shared ancestry) between the dog, human and mouse genome is very high. The majority of genes contain no sequence gaps, which is a great aid to scientists seeking to test particular genes as candidates for diseases.

Over the course of its evolution, the canine genome acquired more than two million SNPs, which are proving invaluable for understanding the role of genetic variation both within and between breeds. Such SNPs, analyzed using DNA chips or bead arrays, will be important for scientists conducting whole-genome association studies aimed at identifying genes that underlie complex traits in the dog. A dog chip with about 127,000 SNPs is currently available, allowing scientists to interrogate the dog genome at several thousand positions simultaneously. When the data from dogs with a given disease, for instance lymphoma, are compared to those from dogs without the disease, we can quickly pinpoint regions of the genome where disease genes are likely to lie.

The Shape of Things

The first important molecular study aimed at understanding the genetics of canine morphology was done at the University of Utah and led by Gordon Lark and Kevin Chase. The project, termed the Georgie Project in memory of a favored dog, focused on the Portuguese water dog, which is ideal for this type of study because it derives from a small number of founders, largely from two kennels, that came to the United States in the early 1950s. The breed standard permits a significant amount of variation in body size compared with other breeds. The community supporting the project is composed of highly motivated owners and breeders who have sought to improve the health of the breed through collaboration with scientists.

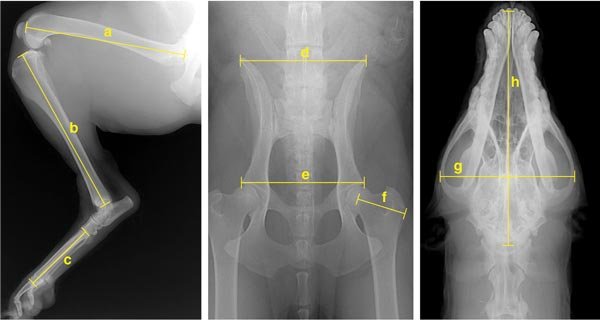

To date, the project has collected DNA from more than 1,000 dogs and has completed a genome-wide scan using more than 500 microsatellite markers on nearly 500 dogs. In addition to family history and medical data, more than 90 measurements have been collected for nearly 500 animals. These were derived from a set of five x-rays taken at the time of initial sample collection. Analysis of these metrics led to the development of four primary principal components (PCs), sets of correlated traits that define Portuguese water dog morphology. It is important to keep in mind that PCs are not genes but traits, and as such, they are susceptible to genetic analysis.

Analysis of the genome scan data and four PCs initially highlighted 44 putative quantitative trait loci (QTLs) on 22 chromosomes that are important for heritable skeletal phenotypes in the Portuguese water dog. QTLs derive from complicated statistical analysis and indicate locations in the genome that contribute coordinately to a particular trait. Of particular interest to us was a locus on canine chromosome 15 (CFA15) that showed a strong association with overall body size. Although this was only one of seven loci hypothesized to play a role in body size in the dog, we chose it as an initial focus because of the strength of the effect and the proximity to a compelling candidate gene.

To find the gene on CFA15, we searched for SNPs in a 15 million-base-pair region and then genotyped the resulting set of markers on all the Portuguese water dogs for which size information was available. The distribution of these markers displayed a single peak close to the insulin-like growth factor-1 gene (IGF1), which is known to influence body size in humans and mice. We investigated IGF1 in detail and showed that 96 percent of Portuguese water dog chromosomes carry one of just two patterns of alleles, which are termed haplotypes. The haplotype associated with small dogs was termed “B” and the one associated with large dogs “I.” Portuguese water dogs homozygous for haplotype B—that is, dogs that have the B pattern on both chromosomes—have the smallest median skeletal size, whereas dogs homozygous for I are largest. Dogs that are heterozygous—that is, those with a different pattern on each chromosome—fall between.

To study the presumably more general role of IGF1 in size differentiation among breeds, we surveyed genetic variation associated with 122 SNPs, spanning the relevant 34 million- to 49 million-base-pair interval of chromosome 15 in 353 dogs representing 14 small breeds and 9 giant breeds. Several lines of evidence pointed to IGF1 as the gene likely to account for small body size in the dogs.

Sexual Dimorphism

The study of the Portuguese water dog has filled in some additional pieces of this interesting puzzle. This vignette has its roots in the original observation that a locus on chromosome 15, which may or may not be IGF1, interacts with other genes to make males larger and females smaller.

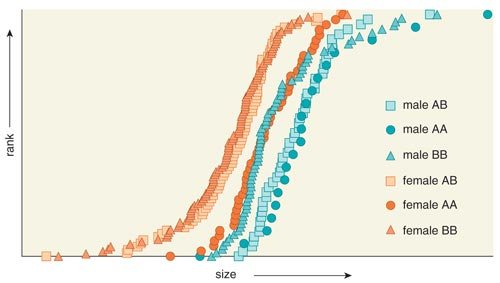

On average, female Portuguese water dogs are 15 percent smaller then males. Chase, Lark and their colleagues observed that in females, a particular haplotype is dominant for small body size. In males, a different set of variants (another unique haplotype) associated with large overall body size is dominant. The locus on CFA15 interacts with another locus on the X chromosome that is known to escape inactivation, meaning that both copies of the genes in this region are turned on (in most locations on the X, only one copy is active).

Two observations from the study must be accounted for in the development of any model to explain canine sexual dimorphism. The explanation must include a discussion of the reversal of dominant haplotypes between males and females associated with CFA15 locus as well as an explanation for the interaction between the CFA15 and X-chromosome loci.

To address the first question, Chase and his colleagues propose the existence of another sex-specific factor. For example, the CFA15 locus might contain two distinct genes associated with two haplotypes; the so-called Ahaplotype acts in both males and females to upregulate size, while the B haplotype and its associated allelesdo not upregulate size but rather contain another gene that suppresses the up-regulator.

The second phenomenon, heterozygote-specific interaction, could be explained by arguing that the activation of haplotype A’s critical upregulator gene requires interaction with a protein produced by the X chromosome.

The data of Chase, Lark and their colleagues are consistent with predictions made in the early 1980s that sexual dimorphism evolves because females secondarily become smaller than males as a result of natural selection for optimal size. Reduction of female size relative to that of males takes place, according to this hypothesis, through an inhibition of major genes that enhance growth, such as the locus on CFA15.

A Faster Dog

The typical whippet, a medium-sized sight hound, is similar in appearance to dogs of the greyhound breed and weighs about nine kilograms. Whippets are characterized by a slim build, long neck, small head and pointed snout. Bully whippets, however, have broad chests and an unusually well-developed leg and neck musculature that makes them unattractive to fanciers of the breed.

Using a candidate gene approach, we showed that individuals with the bully phenotype carry two copies of a two-base-pair deletion in the third exon (a gene region that is transcribed to make portions of proteins) of MSTN, with the result that a truncated or mutant protein is produced. These findings were somewhat expected, as the double-muscle phenotype observed in the whippet is reminiscent of what has been reported in mice, cattle and sheep and in a single case in humans, each of which was caused by a mutation in the myostatin gene. The specifics for dogs, however, were useful to the whippet dog community, which is seeking to develop a genetic test that will reduce the number of dogs produced with the bully phenotype.

Interestingly, we also found that individuals carrying only one copy of the mutation are, on average, more muscular than wild-type individuals, as measured by their neck and chest girth as well as mass-to-height ratio. Indeed, we estimated that mutations in myostatin explain approximately 60 percent of the variation in both the ratio of height to weight and neck girth, and 31 percent of the variation in chest size. In addition to the statistically significant differences between dogs that were bully and wild types, dogs who carried one copy of the variant allele were more heavily muscled then their wild-type counterparts, although not nearly as heavily muscled as the bully dogs.

This observation caused us to ask whether dogs that carried one copy of the mutation were faster racers—a success that would likely lead them to be bred more, which in turn could produce bully dogs if two recessive-gene individuals were paired. Careful analysis revealed an association between individuals carrying one copy of the MSTN mutation and racing speed. Dogs that were the faster racers (class A) were more likely to carry the mutation then were dogs that were slower racers (classes B, C and D). Least likely to carry the mutation were dogs that had never raced and were primarily show dogs.

We considered the possibility that the result could be explained solely by the fact that A racers tended to be mated more often to A racers as opposed to B, C, D or nonracing dogs. This tendency would predict a significant amount of population substructure among A racing dogs. Although we demonstrated that some population substructure exists, we were able to show that it did not fully account for the observation that an excess of A racing dogs carried the myostatin mutation compared to dogs that either did not race or were class B, C or D. Indeed, 50 percent of the A racers tested carried the mutation. We did not find the variant in greyhounds or any of the heavily muscled mastiff breeds such as the bulldog.

Remaining Selective

The advances of the past three years in canine genetics have been enormous. The dog genome has been mapped and sequenced. A host of disease loci have been mapped, and in many cases the underlying mutations identified. Our understanding of how dog breeds relate to one another is beginning to develop, and we have a fundamental understanding of the organization of the canine genome. The issue of complex traits is no longer off-limits. We have begun to understand the genetic portfolio that leads to variation in body size and shape, and even some performance-associated behaviors.

Certainly the next few years will bring an explosion of disease-gene mapping. The genetics of canine cancer, heart disease, hip dysplasia, vision and hearing anomalies have all been areas of intense study, and investigators working on these problems are poised to take advantage of the recent advances described here. Whole-genome association studies are likely to replace family-based linkage studies as a way of finding genes associated with not only disease susceptibility and progression, but morphology and behavior as well.

What will the companion-animal and scientific communities do with this new information? It is certainly hoped that the disease-gene mapping will lead to the production of genetic tests and more thoughtful breeding programs associated with healthier, more long-lived dogs. It will be easier to select for particular physical traits such as body size or coat color, not only because we understand the underlying genetic pathways, but because genetic tests are likely to be made available as quickly as results are published. Finally, canine geneticists will finally have a chance to develop an understanding of the genes that cause both breed-specific behaviors (why do pointers point and herders herd?).

What is far less clear is whether we will come to understand what makes the domestic dog unique to us among all the animals in the mammalian world. We have domesticated dogs to the point that they display loyalty, friendship and companionship. We seek their company and approval and bring them into our homes, often as equal members of our family. We rejoice in their victories and mourn their deaths, often as we celebrate or mourn our own children. Is the genetics that defines this relationship within the dog, within ourselves, or both? None of the studies proposed are likely to answer that question, and perhaps that is okay. The comparative-genome projects of humans and dogs were designed to bring about an understanding of our similarities and differences. Perhaps scientists will have to be satisfied to understand that much, and leave as a mystery the genetic basis of approval, adoration and loyalty. At least for me and my dog, it’s enough.

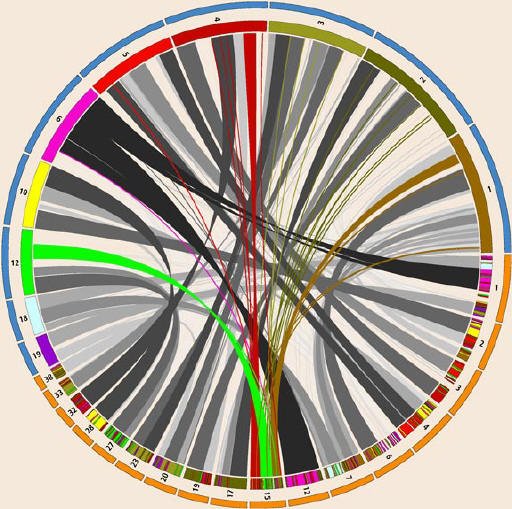

Picturing Dog-Human Homology

The sequencing of the dog genome, completed in 2005, revealed large overlaps between the dog and human genomes. Some of the patterns in dog-human homology—similarity arising from shared ancestry—are depicted here in a circular diagram created by Martin Krzywinski of Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre in Vancouver, British Columbia. Selected human (top, blue outer band) and dog (bottom, orange outer band) chromosomes are arranged around the circle, with bands connecting regions of homology between the two species. Where DNA on a dog chromosome matches human DNA, color-coded stripes indicate the relevant human chromosome. The spray of colored ribbons on the cover illustration shows the pattern of connections between dog chromosome 15 and seven human chromosomes.

Bibliography

- Chase, K., et al. 2002. Genetic basis for systems of skeletal quantitative traits: Principal component analysis of the canid skeleton. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the U.S.A. 99:9930-9935.

- Chase, K., D. F. Carrier, F. R. Adler, E. A. Ostrander and K. G. Lark. 2005. Interaction between the X chromosome and an autosome regulates size sexual dimorphism in Portuguese Water Dogs. Genome Research 15:1820-1824.

- Lindblad-Toh, K., et al. 2005. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438:803-819.

- Mosher, D., et al. In press. Performance enhancing polymorphisms: A protein truncating mutation in the canine myostatin gene leads to extensive over muscling in homozygote dogs and enhanced racing performance in heterozygote carriers. PLoS Genetics.

- Parker, H. G., et al. 2004. Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog. Science 304:1160-1164.

- Parker, H. G., and Ostrander, E. A. 2005. Canine genomics and genetics: Running with the pack. PLoS Genetics 1(5): e58.

- Sutter, N. B., et al. 2007. A single IGF1 allele Is a major determinant of small size in dogs. Science 316:112-115.

- Sutter, N. B., et al. 2004. Extensive and breed-specific linkage disequilibrium in Canis familiaris. Genome Research 14:2388-2396.